Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

The City College of New York

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Related

1

Drugs associated with The City College of New YorkTarget |

Mechanism ICAM-1 inhibitors [+1] |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePending |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

32

Clinical Trials associated with The City College of New YorkNCT06872164

Onsite PTSD Treatment to Improve MOUD Outcomes: Open Pilot Trial of Stakeholder-engaged Adapted Cognitive Processing Therapy

The goal of this open pilot trial is to learn if an adapted version of Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), delivered through telehealth, can treat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults who use syringe services programs. The main questions it aims to answer are:

* Can the intervention be done in syringe services programs?

* Are syringe services program clients and staff open to the intervention?

* Can the intervention lower PTSD symptoms and help participants keep taking their medication for opioid use disorder (ex. Buprenorphine or methadone)?

Participants will:

* Attend 4-18 tele-delivered CPT sessions at the syringe services program

* Complete between-session CPT practice with the support of SSP-based "coaches"

* Meet with research staff monthly to complete surveys of their PTSD symptoms, drug use, and mental health

* Can the intervention be done in syringe services programs?

* Are syringe services program clients and staff open to the intervention?

* Can the intervention lower PTSD symptoms and help participants keep taking their medication for opioid use disorder (ex. Buprenorphine or methadone)?

Participants will:

* Attend 4-18 tele-delivered CPT sessions at the syringe services program

* Complete between-session CPT practice with the support of SSP-based "coaches"

* Meet with research staff monthly to complete surveys of their PTSD symptoms, drug use, and mental health

Start Date02 Jun 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06769321

Phase 2 RCT Automatic Thermomechanical Massage Bed for Acute Pain Relief for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain

This prospective, double-blinded, sham-control, parallel-arm, randomized pilot trial will recruit n=40 participants, ages 18-65 (inclusive), with chronic low back pain (LBP) in the lower region, to be randomly assigned using 1:1 randomization method to receive a 40-minute single session of either active or sham Automated Thermo-mechanical Therapy (ATT). All research procedures, including informed consent, ATT session, and pre- and post-ATT assessments, will be completed in one single session.

Start Date05 Jun 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06528366

High Definition Transcranial Continuous Current Stimulation and Consumption of Chlorella Pyrenoidosa as Adjuvant Treatment for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Reduced ejection fraction heart failure (HFrEF) is a complex and multifactorial condition. It is characterized by a decrease in the ability of the left ventricle to eject blood effectively during systole, resulting in an ejection fraction of less than 40%. This insufficiency in blood pumping leads to inadequate tissue perfusion and a series of adverse physiological adaptations that further compromise cardiac function, representing an important challenge in conducting treatment. The pathophysiology of HFrEF involves multiple mechanisms starting from the remodeling of the left ventricle in the face of some initial aggression, such as a heart attack, which culminates in a progressive deterioration of the contractile function. Additionally, neurohormonal systems are activated in response to the decrease in cardiac output, resulting in hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, which leads to the activation of inflammatory cascades, mainly involving Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-alfa), and disease progression. HFrEF is more prevalent in elderly populations and leads to increased hospital admissions. Furthermore, B12 depletion is more common in the elderly population and these two associated factors, functional impairment of the heart, disruption in the inflammatory cascade and depletion of nutrients, such as vitamin B12, can impact patients; quality of life in the long term. The reduction in B12 levels leads to changes in the cardiac and brain systems, due to the increase in homocysteine and the triggering of the inflammatory cascade. B12 supplementation through Chlorella Pyrenoidosa (microalgae - functional food) reduces cardiac damage and modulate the inflammatory cascade. And also High-Density Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (HD-tDCS), a non-invasive technique capable of modulating neuronal excitability and inducing anti-inflammatory effects. In this sense, the objective is to evaluate the effects of HD-tDCS and the consumption of Chlorella Pyrenidosa to improve B12 levels and inflammatory response in patients with HFrEF.

Start Date26 Sep 2023 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with The City College of New York

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with The City College of New York

Login to view more data

12,388

Literatures (Medical) associated with The City College of New York01 Aug 2025·Addictive Behaviors

Relations between adverse childhood experiences, racial and ethnic Identity, and cannabis use outcomes

Article

Author: Espinosa, Adriana ; Gette, Jordan A

01 Jun 2025·Clinical Neurophysiology

Electrophysiological hemispheric asymmetries induced by parietal stimulation eliciting visual percepts

Article

Author: Savazzi, S ; Parra, L C ; Bertacco, E ; Mazzi, C ; Bonfanti, D

01 Jun 2025·Optics Communications

Supercontinuum light generated in water with small and large scattering particles

Author: Bin Mazhar, Shah Faisal ; Alfano, Robert

13

News (Medical) associated with The City College of New York10 Jun 2024

Value-based care may be the topic with the greatest representation on the AHIP agenda this year, and that likely comes as no surprise.

Thought leaders from across the insurance industry will descend on Las Vegas this week for AHIP's annual conference, kicking off three days of discussions on the biggest issues facing payers.

The Fierce Health Payer team will also be making the journey to Sin City, so keep an eye out for our coverage over the next several days. Ahead of the event, here's a look at three key trends we expect to hear plenty about across panels, keynotes and meetings.

Are there topics you're looking for? Let Noah Tong and I know on social media, and keep a lookout for us at the show!

GLP-1 costs and shortages remain center-stage

Challenges with the cost of and access to GLP-1 products continue to be top of mind for healthcare leaders, and the insurance sector is no exception.

Sessions Wednesday will kick off with a panel on these drugs and the potenial they present in addressing obesity. The panel will feature speakers from Highmark, NYU Langone Health, WeightWatchers and the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review.

GLP-1s will also feature in multiple panels and presentations throughout the week.

Multiple payers and pharmacy benefit managers have launched weight and obesity management programs over the past year, and a key focus within those initiatives is ensuring the patients who need these drugs can access them and that they're being used appropriately.

As the data grow on these products and their efficacy, both government and private insurers have widened coverage.

Continued talk about the implementation of value-based care

Value-based care may be the topic with the greatest representation on the AHIP agenda this year, and that likely comes as no surprise. Payers want to make these models work, given the potential for savings and improved outcomes, but implementation challenges remain.

Panels at the conference include a focus on value-based specialty services, the role VBC can play in addressing health equity and disparities and the strategies necessary to make these models sustainable.

Other segments will also delve into the public health infrastructure and what can be done to enhance this critical segment. AHIP will host a two-part keynote on public health featuring speakers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente, the White House's Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy, the City College of New York and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Value-based care lessons from Medicare Advantage and the state of that program are also on the docket.

Cutting through the AI hype

There is plenty of intrigue—and fear—about the potential of AI in healthcare.

AHIP will open Thursday's sessions with a panel that aims to break through the noise and dig into the promise of this technology to revolutionize healthcare. It will feature speakers from AmeriHealth Caritas, Microsoft, the National AI Advisory Committee and AHIP itself.

The conference will also host a panel on striking the balance between the human connection in healthcare and critical technological innovation.

12 Jan 2024

Researchers are using crystallography to gain a better understanding of how proteins shapeshift. The knowledge can provide valuable insight into stopping and treating diseases.

Proteins do the heavy lifting of performing biochemical functions in our bodies by binding to metabolites or other proteins to complete tasks. To do this successfully, protein molecules often shape-shift to allow specific binding interactions that are needed to perform complex, precise chemical processes.

A better understanding of the shapes proteins take on would give researchers important insight into stopping or treating diseases, but current methods for revealing these dynamic, three-dimensional forms offer scientists limited information. To address this knowledge gap, a team from the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC) designed an experiment to test whether performing X-ray crystallography imaging using elevated temperature versus elevated pressure would reveal distinct shapes. The results of the team's work appear in the journal Communications Biology.

"Protein structures don't sit still; they shift between several similar shapes much like a dancer," said the study's principal investigator Daniel Keedy, Ph.D., a professor with the CUNY ASRC's Structural Biology Initiative and a chemistry and biochemistry professor at The City College of New York and the CUNY Graduate Center. "Unfortunately, existing approaches for viewing proteins only reveal one shape, or suggest the presence of multiple shapes without providing specific details. We wanted to see if different ways of poking at a protein could give a us a more detailed view of how it shape-shifts."

For their experiment, the team obtained crystals of STEP, also known as PTPN5 -- a drug target protein for the treatment of several diseases, including Alzheimer's -- and agitated them using either high pressure (2,000 times the Earth's atmospheric pressure) or high temperature (body temperature), both of which are very different from typical crystallography experiments at atmospheric pressure and cryogenic temperature (-280 F, -173 C). The researchers viewed the samples using X-ray crystallography and observed that high temperature and high pressure had different effects on the protein, revealing distinct shapes.

While high pressure isn't a condition that proteins experience inside the body, Keedy said the agitation method exposed different structural states of the protein that may be relevant to its activity in human cells.

"Having the ability to use perturbations such as heat and pressure to elucidate these different states could give drug developers tools for determining how they can trap a protein in a particular shape using a small-molecule drug to diminish its function," Keedy added.

PROTACs

14 Sep 2023

New research shows how we prefer art that speaks to our sense of self. The findings could lead to more effective forms of art therapy, but can also lead media companies to generate addictive content online.

People have fairly consistent preferences when it comes to judging the beauty of things in the real world -- it's well known, for example, that humans prefer symmetrical faces. But our feelings about art may be more personal, causing us to prefer art that speaks to our sense of self, research in Psychological Science suggests.

"When there is personal meaning in an image, that can dominate your aesthetic judgments way more than any image feature," said Edward A. Vessel (The City College of New York) in an interview. Though self-relevant artwork features images related to a person's own identity, memories, and interests, it can serve not only as a "mirror for the self" but as a window into the experiences of other people, Vessel said.

"When we can relate [a piece of art] to our own experience, that's like giving us a key to unlock deeper levels of meaning -- a deeper understanding of the other through mapping it onto our own lived experience," he said.

Findings on self-relevance and aesthetic appeal could be used for good to create more effective forms of art therapy, but they can also be abused by media companies looking to use consumer models to generate addictive content on social media and other platforms, Vessel warned.

"I almost see this work that we're doing as similar to work on the addictiveness of tobacco back when companies knew it was addictive but weren't telling the public," Vessel said. "By understanding this and how personally relevant information can be highly engaging, we can be in a better position to create policies around its use and misuse."

Vessel and colleagues explored how self-relevance influences the aesthetic appeal of artwork through a series of studies in which participants evaluated real and synthetically personalized art.

Because there was no existing method for measuring this relationship, the researchers began by testing if their experimental design detected associations between self-relevance and aesthetic appeal. They accomplished this through two initial studies in which 33 in-person German-speaking and 208 online English-speaking participants rated art from global museum collections based on how beautiful, moving, and self-relevant they perceived the images to be. In this first study, participants were asked to rate each artwork's self-relevance based on the extent to which it related to "things and events that define you as a person." In the second study the term was left undefined.

Both studies suggested that self-relevance has a large effect on the perceived beauty and meaning of an image, Vessel and colleagues wrote. Participants in both studies perceived self-relevant images to be the most aesthetically appealing, with self-relevance accounting for 28% of the variance in participants' aesthetic appeal ratings in the first study.

In a subsequent study, Vessel and colleagues asked 45 German participants to evaluate a new set of images. Unlike in the previous study, however, the participants first completed a questionnaire that captured their demographic information, childhood residence, key autobiographical memories, personal interests, and regular activities. The researchers then used this information to create a set of 20 personalized synthetic artworks by transforming related source images with a style-transfer algorithm, which can apply an existing artistic style to a photograph.

After these images were created, each participant rated a set of 80 images that included their personalized synthetic artwork, synthetic artwork created for another participant, generic synthetic artwork, and real artwork from a museum.

Participants rated self-relevant synthetic artwork as more aesthetically appealing than other-relevant synthetic art or real artwork, although the latter was preferred over generic synthetic art.

"Generating new artworks with self-relevant content that related to a participant's lived experience, identity, and interests was highly effective at increasing aesthetic appeal," the researchers wrote.

When the researchers took a closer look at which aspects of self-relevance were driving this effect, they found that synthetic images related to participants' autobiographical memories, identity, preferences, and interests were rated as more appealing, but those related to their daily activities and goals were not. This suggests that art needs to tap more deeply into a person's self-construct in order to generate this effect, Vessel said.

Vessel plans to continue this work by further examining which aspects of a person's self-construct influence aesthetic appeal, as well as more closely studying how the brain's default mode network and other mechanisms may support this effect.

Clinical Result

100 Deals associated with The City College of New York

Login to view more data

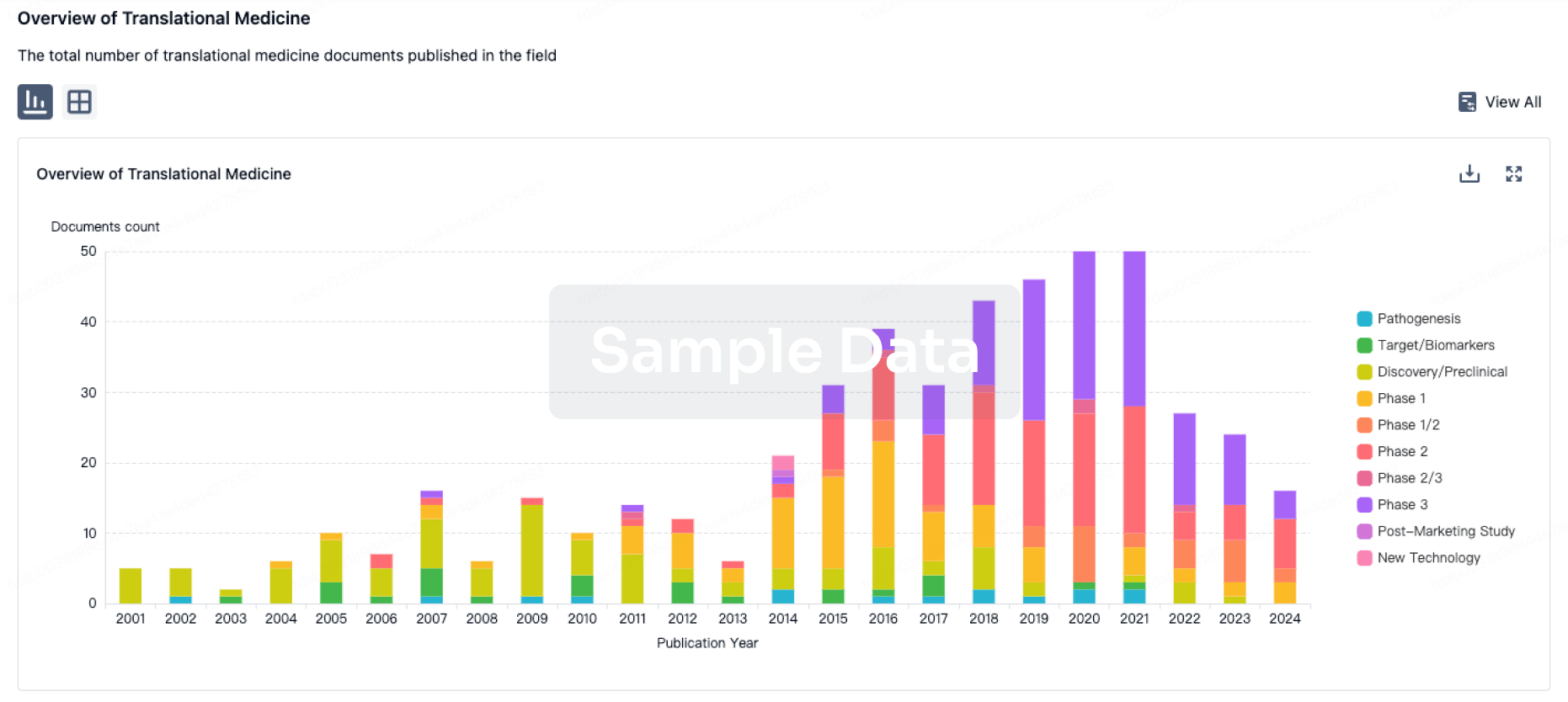

100 Translational Medicine associated with The City College of New York

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 04 Jun 2025

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Other

1

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

ICAM-Lcn2-LP ( ICAM-1 x LCN2 ) | Triple Negative Breast Cancer More | Pending |

Login to view more data

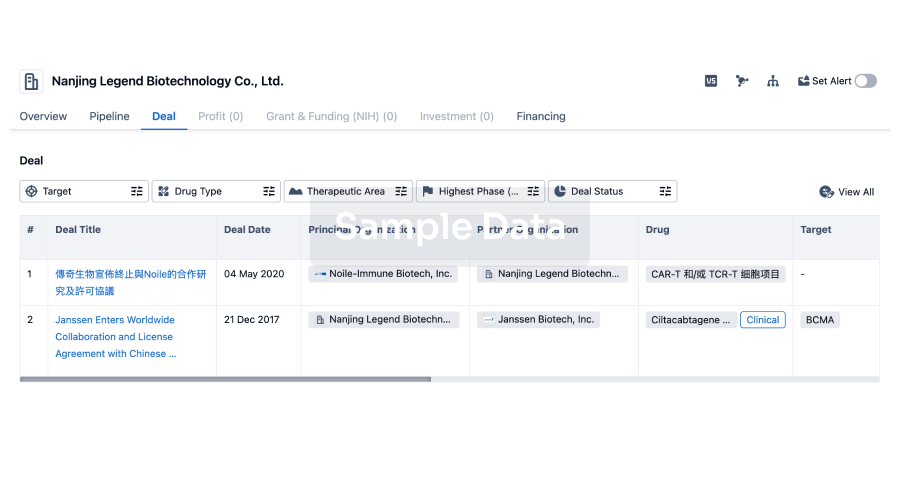

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

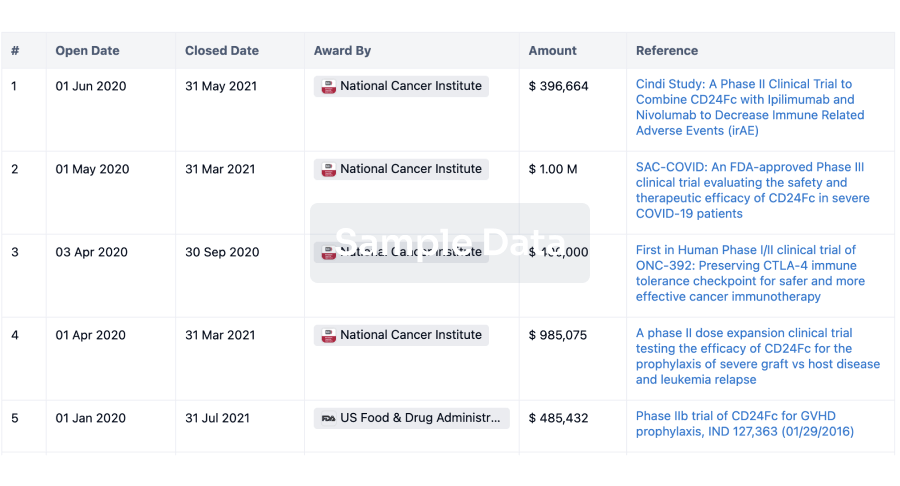

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

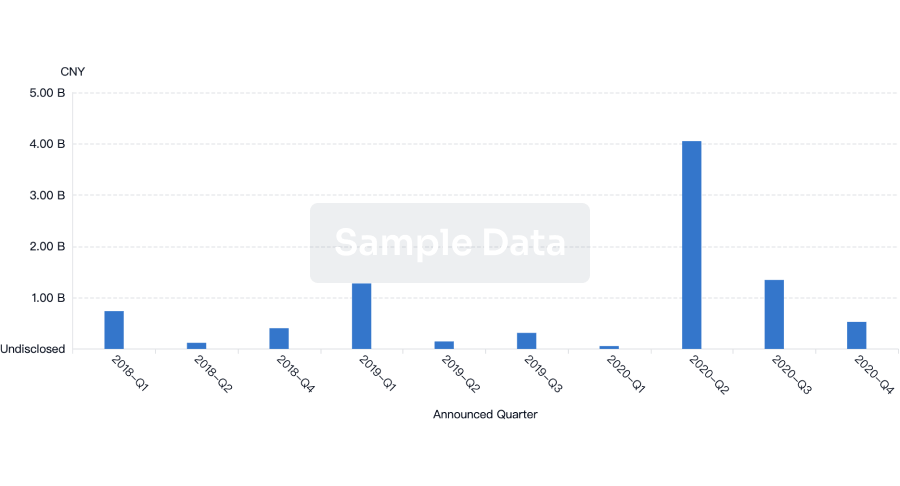

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free